Step by Step Tutorial for Jekyll

1. Setup

gem install jekyll bundler

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Home</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello World!</h1>

</body>

</html>

Welcome to Jekyll’s step-by-step tutorial. The goal of this tutorial is to take you from having some front end web development experience to building your first Jekyll site from scratch — not relying on the default gem-based theme. Let’s get into it!

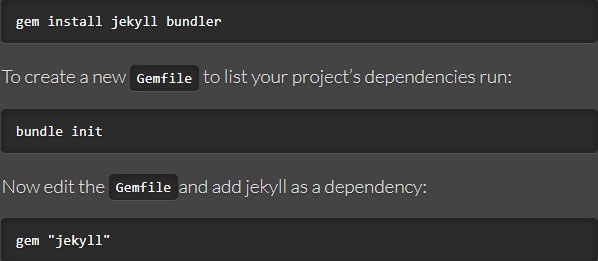

Installation

Jekyll is a Ruby program so you need to install Ruby on your machine to begin with. Head over to the install guide and follow the instructions for your operating system.

With Ruby setup you can install Jekyll by running the following in your terminal:

Finally run bundle to install jekyll for your project.

You can now prefix all jekyll commands listed in this tutorial with bundle exec

to make sure you use the jekyll version defined in your Gemfile.

Create a site

It’s time to create a site! Create a new directory for your site, you can name it whatever you’d like. Through the rest of this tutorial we’ll refer to this directory as “root”.

If you’re feeling adventurous, you can also initialize a Git repository here. One of the great things about Jekyll is there’s no database. All content and site structure are files which a Git repository can version. Using a repository is completely optional but it’s a great habit to get into. You can learn more about using Git by reading through the Git Handbook.

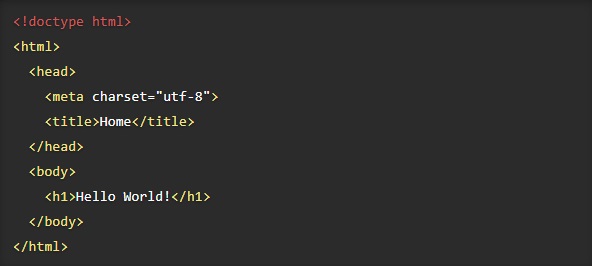

Let’s add your first file. Create index.html in the root with the following

content:

Build

Jekyll is a static site generator so we need Jekyll to build the site before we can view it. There are two commands you can run in the root of your site to build it:

jekyll build- Builds the site and outputs a static site to a directory called_site.jekyll serve- Does the same thing except it rebuilds any time you make a change and runs a local web server athttp://localhost:4000.

When you’re developing a site you’ll use jekyll serve as it updates with any

changes you make.

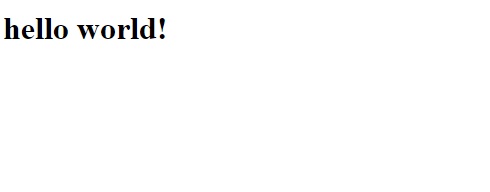

Run jekyll serve and go to

http://localhost:4000 in

your browser. You should see “Hello World!”.

Well, you might be thinking what’s the point in this? Jekyll just copied an HTML file from one place to another. Well patience young grasshopper, there’s still much to learn!

2. Liquid

Liquid is where Jekyll starts to get more interesting. Liquid is a templating language which has three main parts: object , tag ,and filter.

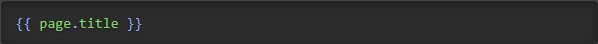

Object

Objects tell Liquid where to output content.They’re denoted by double curly braces: For Example

Output will be Title of the page.

Tags

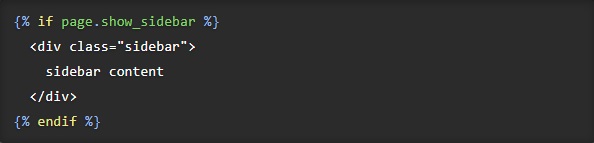

Tags create the logic and control flow for templates. They are denoted by curly braces and percent signs.For Example:

Outputs the sidebar if page.show_sidebar is true.

Filters

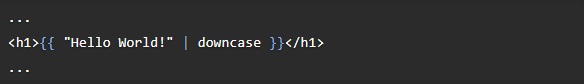

Filters change the output of a Liquid object. They are used within an output

and are separated by a |. For example:

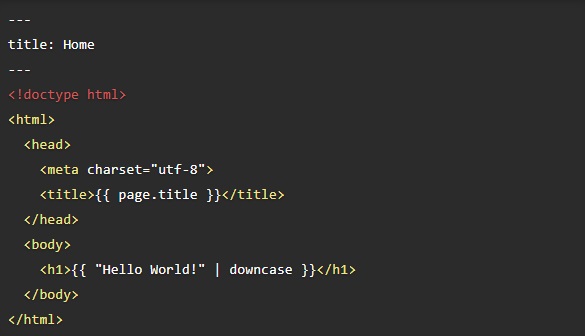

Use Liquid

Now it’s your turn, change the Hello World! on your page to output as lowercase:

It may not seem like it now, but much of Jekyll’s power comes from combining Liquid with other features.

In order to see the changes from downcase Liquid filter, we will need to add front matter.

That’s next. Let’s keep going.

3. Front Matter

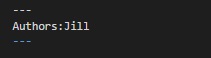

Front matter is a snippet of YAML which sits between two triple-dashed lines at the top of a file. Front matter is used to set variables for the page, for example:

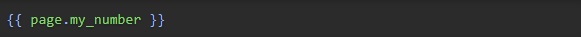

Front matter variables are available in Liquid under the page variable. For

example to output the variable above you would use:

Use front matter

Let’s change the <title> on your site to populate using front matter in index.html:

You may still be wondering why you’d output it this way as it takes more source code than raw HTML. In this next step, you’ll see why we’ve been doing this.

4. Layouts

Websites typically have more than one page and this website is no different.

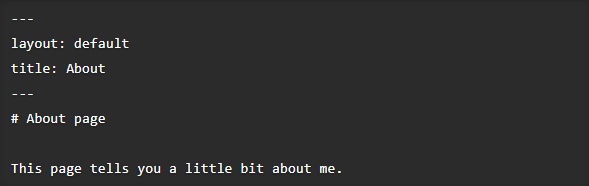

Jekyll supports Markdown as well as HTML for pages. Markdown is a great choice for pages with a simple content structure (just paragraphs, headings and images), as it’s less verbose than raw HTML. Let’s try it out on the next page.

Create about.md in the root.

For the structure you could copy index.html and modify it for the about page.

The problem with doing this is duplicate code. Let’s say you wanted to add a

stylesheet to your site, you would have to go to each page and add it to the

<head>. It might not sound so bad for a two page site, imagine doing it

for 100 pages. Even simple changes will take a long time to make.

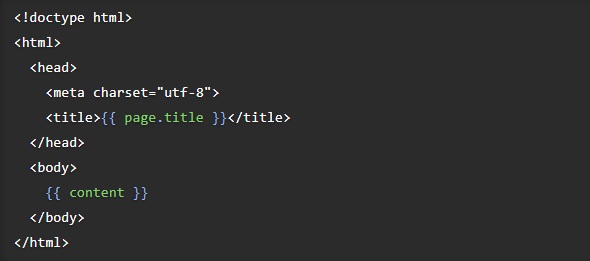

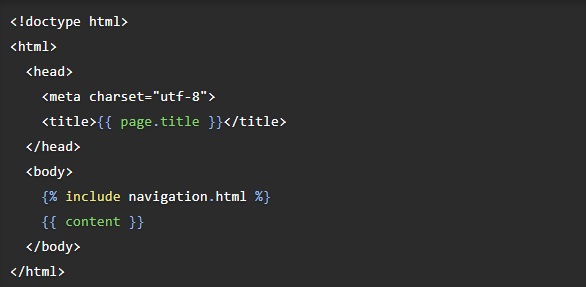

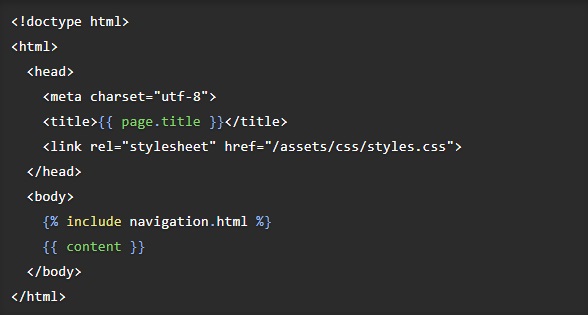

Creating a layout

Using a layout is a much better choice. Layouts are templates that wrap around

your content. They live in a directory called _layouts.

Create your first layout at _layouts/default.html with the following content:

You’ll notice this is almost identical to index.html except there’s

no front matter and the content of the page is replaced with a content

variable. content is a special variable which has the value of the rendered

content of the page it’s called on.

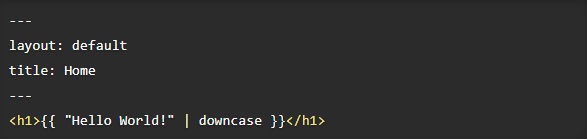

To have index.html use this layout, you can set a layout variable in front

matter. The layout wraps around the content of the page so all you need in

index.html is:

After doing this, the output will be exactly the same as before. Note that you

can access the page front matter from the layout. In this case title is

set in the index page’s front matter but is output in the layout.

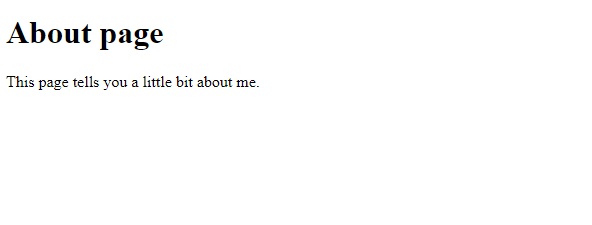

About page

Back to the about page, instead of copying from index.html, you can use the

layout.

Add the following to about.md:

Open http://localhost:4000/about.html in your browser and view your new page.

Congratulations, you now have a two page website! But how do you navigate from one page to another? Keep reading to find out.

5. Includes

The site is coming together; however, there’s no way to navigate between pages. Let’s fix that.

Navigation should be on every page so adding it to your layout is the correct place to do this. Instead of adding it directly to the layout, let’s use this as an opportunity to learn about includes.

Include tag

The include tag allows you to include content from another file stored

in an _includes folder. Includes are useful for having a single source for

source code that repeats around the site or for improving the readability.

Navigation source code can get complex so sometimes it’s nice to move it into an include.

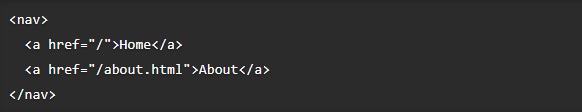

Include usage

Create a file for the navigation at _includes/navigation.html with the

following content:

Try using the include tag to add the navigation to _layouts/default.html:

Open http://localhost:4000 in your browser and try switching between the pages.

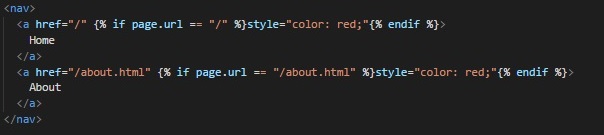

Current page highlighting

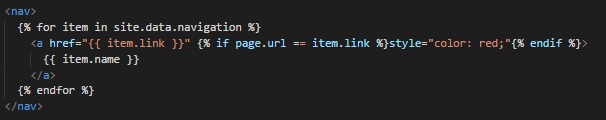

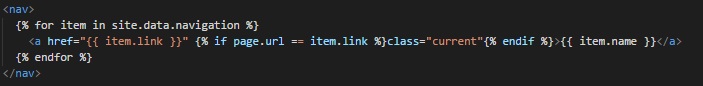

Let’s take this a step further and highlight the current page in the navigation.

_includes/navigation.html needs to know the URL of the page it’s inserted into

so it can add styling. Jekyll has useful variables available

one of which is page.url.

Using page.url you can check if each link is the current page and color it red

if true:

Take a look at http://localhost:4000 and see your red link for the current page.

There’s still a lot of repetition here if you wanted to add a new item to the navigation or change the highlight color. In the next step we’ll address this.

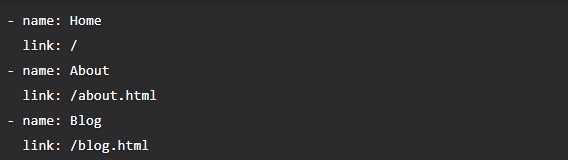

6. Data Files

Jekyll supports loading data from YAML, JSON, and CSV files located in a _data

directory. Data files are a great way to separate content from source code to

make the site easier to maintain.

In this step you’ll store the contents of the navigation in a data file and then iterate over it in the navigation include.

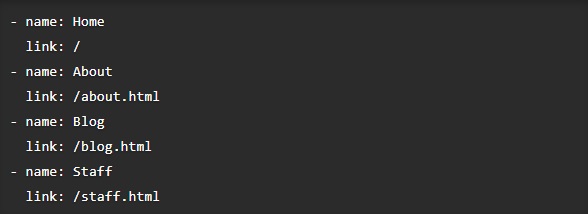

Data file usage

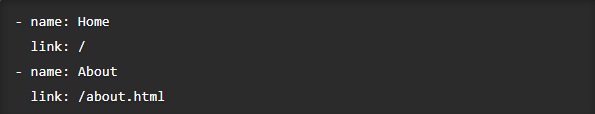

YAML is a format that’s common in the Ruby ecosystem. You’ll use it to store an array of navigation items each with a name and link.

Create a data file for the navigation at _data/navigation.yml with the

following:

Jekyll makes this data file available to you at site.data.navigation. Instead

of outputting each link in _includes/navigation.html, now you can iterate over

the data file instead:

The output will be exactly the same. The difference is you’ve made it easier to add new navigation items and change the HTML structure.

What good is a site without CSS, JS and images? Let’s look at how to handle assets in Jekyll.

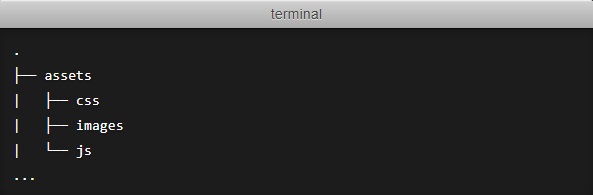

7. Assets

Using CSS, JS, images and other assets is straightforward with Jekyll. Place them in your site folder and they’ll copy across to the built site.

Jekyll sites often use this structure to keep assets organized:

Sass

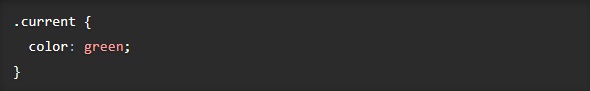

The inline styles used in _includes/navigation.html is not a best practice,

let’s style the current page with a class instead.

You could use a standard CSS file for styling, we’re going to take it a step further by using Sass. Sass is a fantastic extension to CSS baked right into Jekyll.

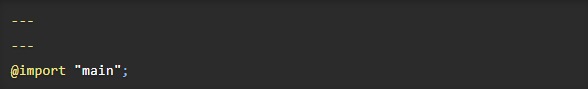

First create a Sass file at /assets/css/styles.scss with the following content:

The empty front matter at the top tells Jekyll it needs to process the file. The

@import "main" tells Sass to look for a file called main.scss in the sass

directory (_sass/ by default which is directly under root folder of your website).

At this stage you’ll just have a main css file. For larger projects, this is a great way to keep your CSS organized.

Create a Sass file at /_sass/main.scss with the following content:

You’ll need to reference the stylesheet in your layout.

Open _layouts/default.html and add the stylesheet to the <head>:

oad up http://localhost:4000 and check the active link in the navigation is green.

Next we’re looking at one of Jekyll’s most popular features, blogging.

8. Blogging

You might be wondering how you can have a blog without a database. In true Jekyll style, blogging is powered by text files only.

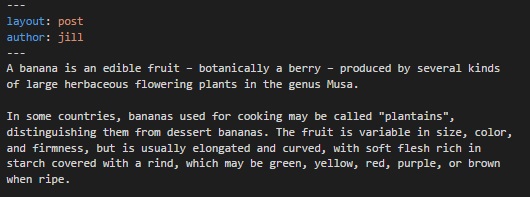

Posts

Blog posts live in a folder called _posts. The filename for posts have a

special format: the publish date, then a title, followed by an extension.

Create your first post at _posts/2018-08-20-bananas.md with the

following content:

This is like the about.md you created before except it has an author and

a different layout. author is a custom variable, it’s not required and could

have been named something like creator.

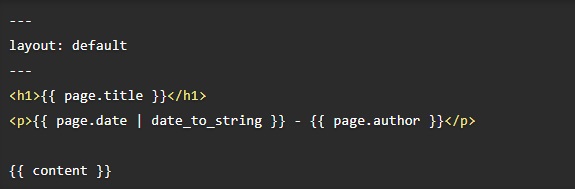

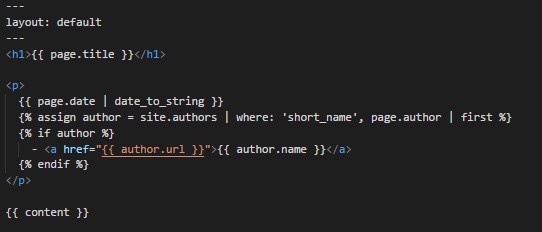

Layout

The post layout doesn’t exist so you’ll need to create it at

_layouts/post.html with the following content:

This is an example of layout inheritance. The post layout outputs the title, date, author and content body which is wrapped by the default layout.

Also note the date_to_string filter, this formats a date into a nicer format.

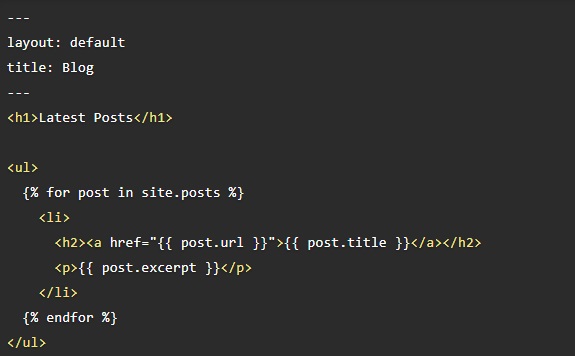

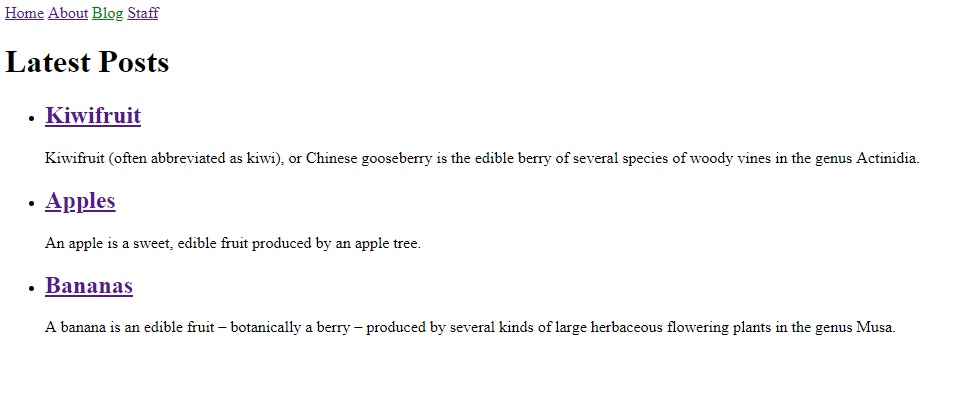

List posts

There’s currently no way to navigate to the blog post. Typically a blog has a page which lists all the posts, let’s do that next.

Jekyll makes posts available at site.posts.

Create blog.html in your root (/blog.html) with the following content:

There’s a few things to note with this code:

post.urlis automatically set by Jekyll to the output path of the postpost.titleis pulled from the post filename and can be overridden by settingtitlein front matterpost.excerptis the first paragraph of content by default

You also need a way to navigate to this page through the main navigation. Open

_data/navigation.yml and add an entry for the blog page:

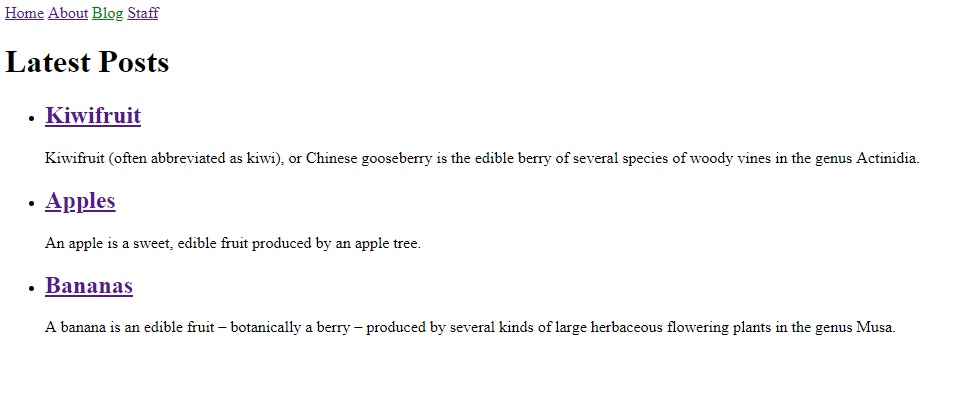

More posts

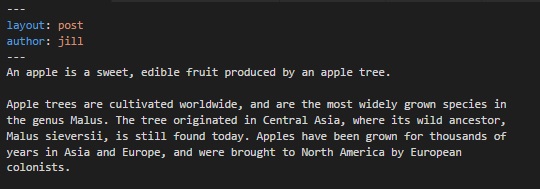

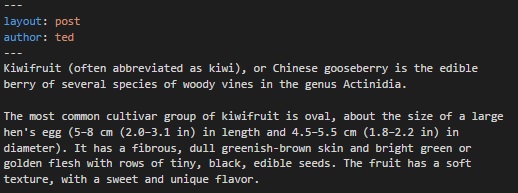

A blog isn’t very exciting with a single post. Add a few more:

_posts/2018-08-21-apples.md:

_posts/2018-08-22-kiwifruit.md:

Open http://localhost:4000 and have a look through your blog posts.

Next we’ll focus on creating a page for each post author.

9. Collection

Let’s look at fleshing out authors so each author has their own page with a blurb and the posts they’ve published.

To do this you’ll use collections. Collections are similar to posts except the content doesn’t have to be grouped by date.

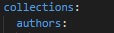

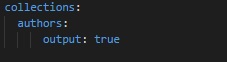

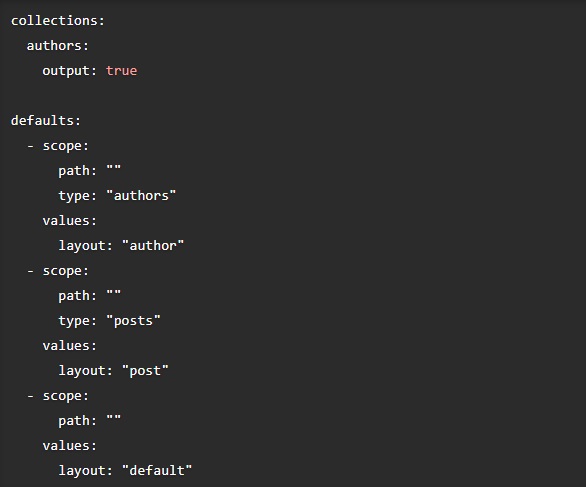

Configuration

To set up a collection you need to tell Jekyll about it. Jekyll configuration

happens in a file called _config.yml (by default).

Create _config.yml in the root with the following:

To (re)load the configuration, restart the jekyll server. Press Ctrl+C in your terminal to stop the server, and then jekyll serve to restart it.

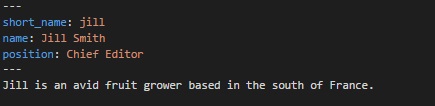

Add authors

Documents (the items in a collection) live in a folder in the root of the site

named _*collection_name*. In this case, _authors.

Create a document for each author:

_authors/jill.md:

_authors/ted.md:

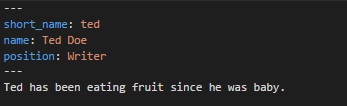

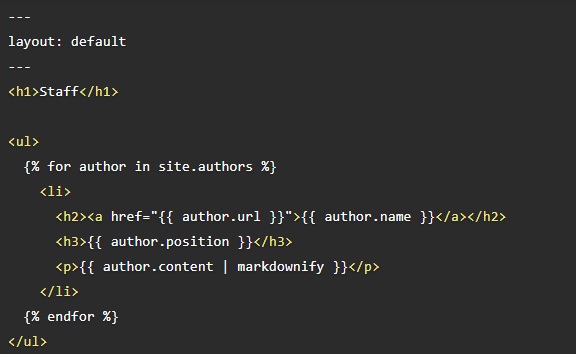

Staff page

Let’s add a page which lists all the authors on the site. Jekyll makes the

collection available at site.authors.

Create staff.html and iterate over site.authors to output all the staff:

Since the content is markdown, you need to run it through the

markdownify filter. This happens automatically when outputting using

{{ content }} in a layout.

You also need a way to navigate to this page through the main navigation. Open

_data/navigation.yml and add an entry for the staff page:

Output a page

By default, collections do not output a page for documents. In this case we want each author to have their own page so let’s tweak the collection configuration.

Open _config.yml and add output: true to the author collection

configuration:

You can link to the output page using author.url.

Add the link to the staff.html page:

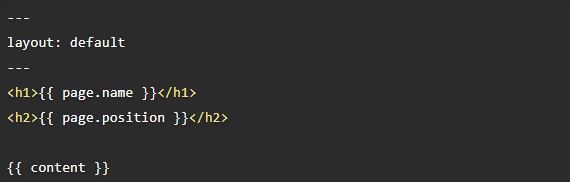

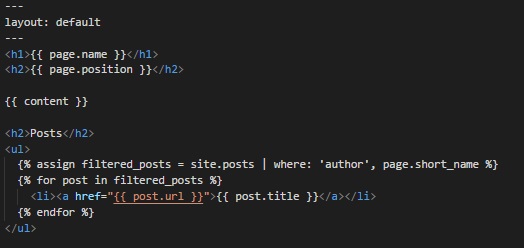

Just like posts you’ll need to create a layout for authors.

Create _layouts/author.html with the following content:

Front matter defaults

Now you need to configure the author documents to use the author layout. You

could do this in the front matter like we have previously but that’s getting

repetitive.

What you really want is all posts to automatically have the post layout, authors to have author and everything else to use the default.

You can achieve this by using front matter defaults

in _config.yml. You set a scope of what the default applies to, then the

default front matter you’d like.

Add defaults for layouts to your _config.yml,

Now you can remove layout from the front matter of all pages and posts. Note

that any time you update _config.yml you’ll need to restart Jekyll for the

changes to take affect.

List author’s posts

Let’s list the posts an author has published on their page. To do

this you need to match the author short_name to the post author. You

use this to filter the posts by author.

Iterate over this filtered list in _layouts/author.html to output the

author’s posts:

Link to authors page

The posts have a reference to the author so let’s link it to the author’s page.

You can do this using a similar filtering technique in _layouts/post.html:

Open up http://localhost:4000 and have a look at the staff page and the author links on posts to check everything is linked together correctly.

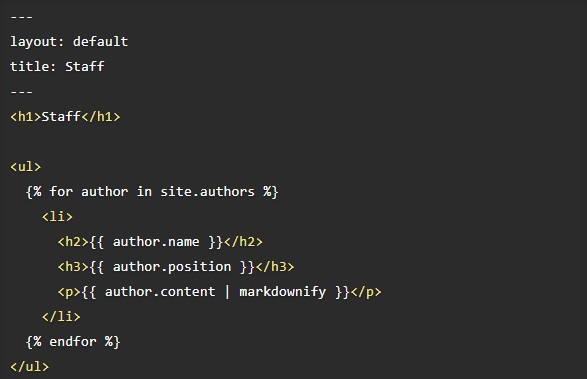

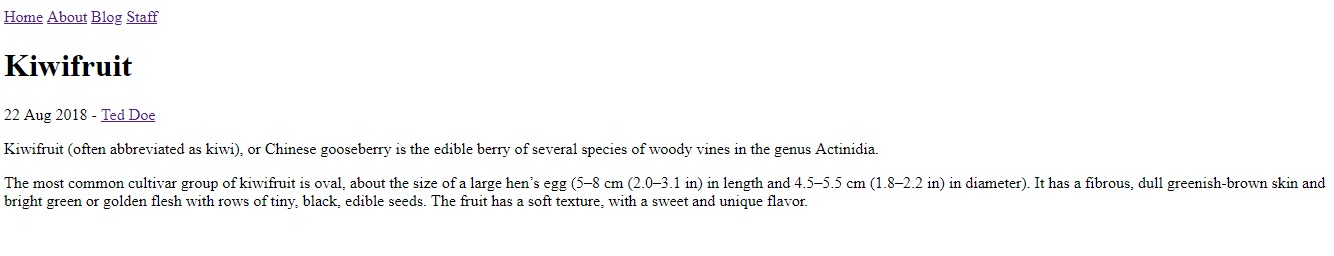

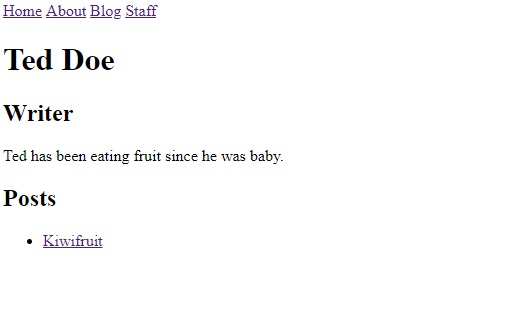

Result

List of Blog post

Blog Information

When click at author in blog it will show author’s information and passing blog

In the next and final step of this tutorial, we’ll add polish to the site and get it ready for a production deployment.

10. Deployment

In this final step we’ll get the site ready for production.

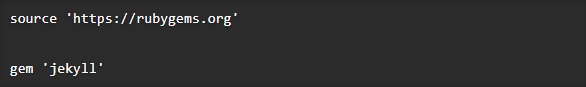

Gemfile

It’s good practice to have a Gemfile for your site. This ensures the version of Jekyll and other gems remains consistent across different environments.

Create Gemfile in the root with the following:

Then run bundle install in your terminal. This installs the gems and

creates Gemfile.lock which locks the current gem versions for a future

bundle install. If you ever want to update your gem versions you can run

bundle update.

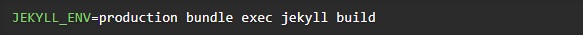

When using a Gemfile, you’ll run commands like jekyll serve with

bundle exec prefixed. So the full command is:

This restricts your Ruby environment to only use gems set in your Gemfile.

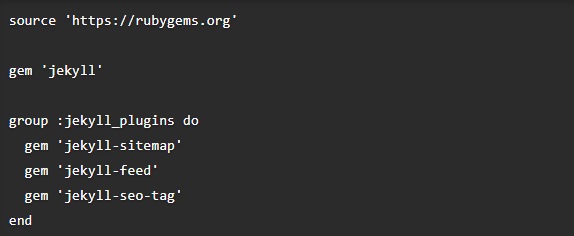

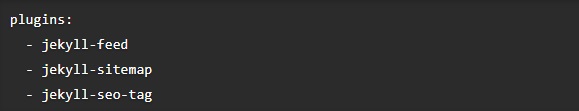

Plugins

Jekyll plugins allow you to create custom generated content specific to your site. There’s many plugins available or you can even write your own.

There’s three official plugins which are useful on almost any Jekyll site:

- jekyll-sitemap - Creates a sitemap file to help search engines index content

- jekyll-feed - Creates an RSS feed for your posts

- jekyll-seo-tag - Adds meta tags to help with SEO

To use these first you need to add them to your Gemfile. If you put them

in a jekyll_plugins group they’ll automatically be required into Jekyll:

Then add these lines to your _config.yml:

Now install them by running a bundle update.

jekyll-sitemap doesn’t need any setup, it will create your sitemap on build.

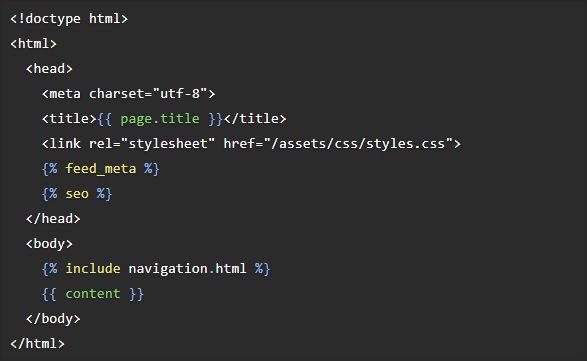

For jekyll-feed and jekyll-seo-tag you need to add tags to

_layouts/default.html:

Restart your Jekyll server and check these tags are added to the <head>.

Environments

Sometimes you might want to output something in production but not in development. Analytics scripts are the most common example of this.

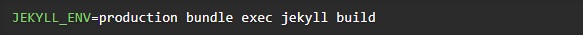

To do this you can use environments. You

can set the environment by using the JEKYLL_ENV environment variable when

running a command. For example:

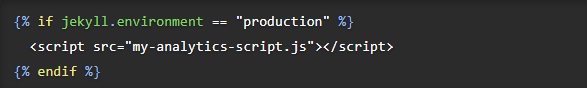

By default JEKYLL_ENV is development. The JEKYLL_ENV is available to you

in liquid using jekyll.environment. So to only output the analytics script

on production you would do the following:

Deployment

The final step is to get the site onto a production server. The most basic way to do this is to run a production build:

And copy the contents of _site to your server.

A better way is to automate this process using a CI or 3rd party.

Wrap up

That brings us to the end of this step-by-step tutorial and the beginning of your Jekyll journey!

- Come say hi to the community forums

- Help us make Jekyll better by contributing

- Keep building Jekyll sites!